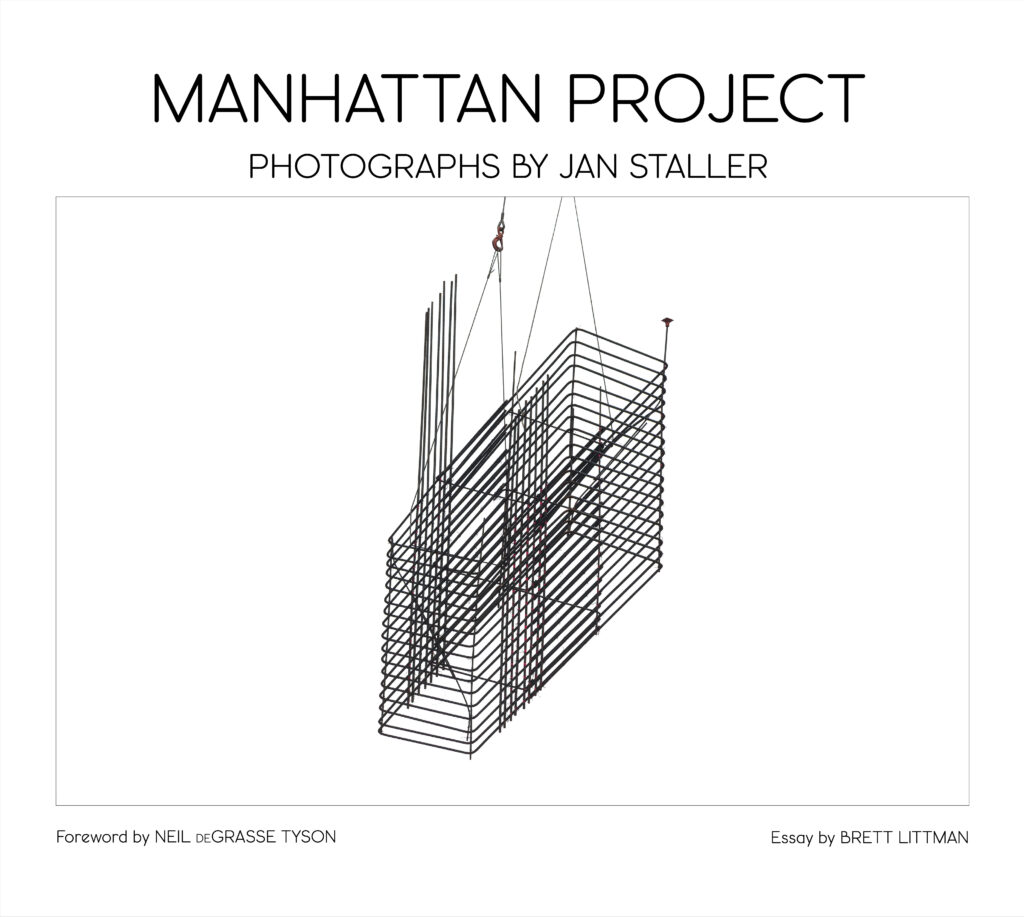

Manhattan Project by Jan Staller

If buildings were stars, then cities would be their galaxies—mass collections of stars, huddled together, distinct and separate from other galaxies across the universe. For most galaxies, those rich in gas, stars continually die and are reborn. When a galaxy runs out of gas, the formation of stars is finished, forever. There also comes a time in the lives of urban dwellers when we ask the naive but serious question: When will all the construction in the City be finished?

As a born-and-raised New Yorker, I did that very calculation while still in high school. First I estimated how long a building lasts, on average. Maybe 25 years? 50 years? 100 years? Let’s say 75 years. Most skylines look completely different after 75 years. The next question was: How many buildings are there? If we limit this mathematical exercise to Manhattan, and obtain data from the Department of City Planning, the number exceeds 100,000. Okay. Let’s say a quarter of them (25,000) are forever-fixtures of the skyline, like Rockefeller Center, the Chrysler Building, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Of course, some structures, believed at the time of construction to be forever, turned out not to be. The original Yankee Stadium (in the Bronx) was demolished and rebuilt in 2010, after 87 years. The Hotel Mayflower on Central Park West was demolished in 2004, after 78 years. The original Hayden Planetarium, completely rebuilt beginning in 1997, lasted 62 years. And the original and ornately decorated Penn Station, demolished in 1963, lasted 53 years.

Continuing the math, if 75,000 buildings are rebuilt every 75 years and not all at once, then that’s 1,000 active construction sites per year in the tiny borough of Manhattan—about thirteen miles long and just over two miles wide at its widest. And today, nothing gets built in a year, so Manhattan would be home to multiple thousands of construction sites at a time. For comparison, the Empire State Building, completed in 1930 as the tallest building in the world, was famously built in 13.5 months.

So the question “When will all the construction in the City be finished?” has one simple answer: Never.

We all walk the streets, frequently redirected by caution signs from construction zones. We get sent under and around scaffolding, as though we were navigating trees in an urban forest of metal poles. Hardly any of us stops to look up or pauses to notice what’s going on over the fence—what the countless construction workers are up to. Like ants building an ant-hill, the workers all look busy, most of the time. But unless you’re a construction worker or an architect, you’re likely clueless about what they’re doing. For starters, how did the crane and the person in the crane get up so high? Yet another mystery of the universe.

We typically ignore what’s going on until the building is done. By then, all we see is steel and glass on the outside, finished walls, floors and ceilings on the inside. With, of course, all the HVAC and mechanicals neatly hidden from view.

That’s too bad.

City-folk are long overdue for a peek at what’s invisible, yet hiding in plain sight. These are the raw materials, tools, and machines that create our homes, our apartments and the places where we work and play. Telescopes won’t get you there. Those are for revealing far away details that your eyes can’t detect.

Microscopes won’t get you there either. Those are for seeing close-up details that your eyes cannot resolve. That peek behind the construction curtain requires an artist. Good artists can get you to notice all that you’ve never noticed before. Or they can force us to look again at whatever we may have taken for granted all our lives.

In the Manhattan Project, which is itself a kind of x-ray view of what buildings are made of, urban photographer Jan Staller isolates, identifies and photographs fundamental elements of the construction worker’s craft. These elements ascend to a form of geometric art, imbued with life, where you can’t help think of I-beams and rebar as the bones and cartilage of the City, where concrete slabs and sheets of metal and glass are a kind of epidermis. And where hooks, pulleys, and diggers are the tools of a mighty force, rendered visible by an artist-photographer who sees what we don’t see, as he reimagines the landscape—the cityscape—that so many of us call home.