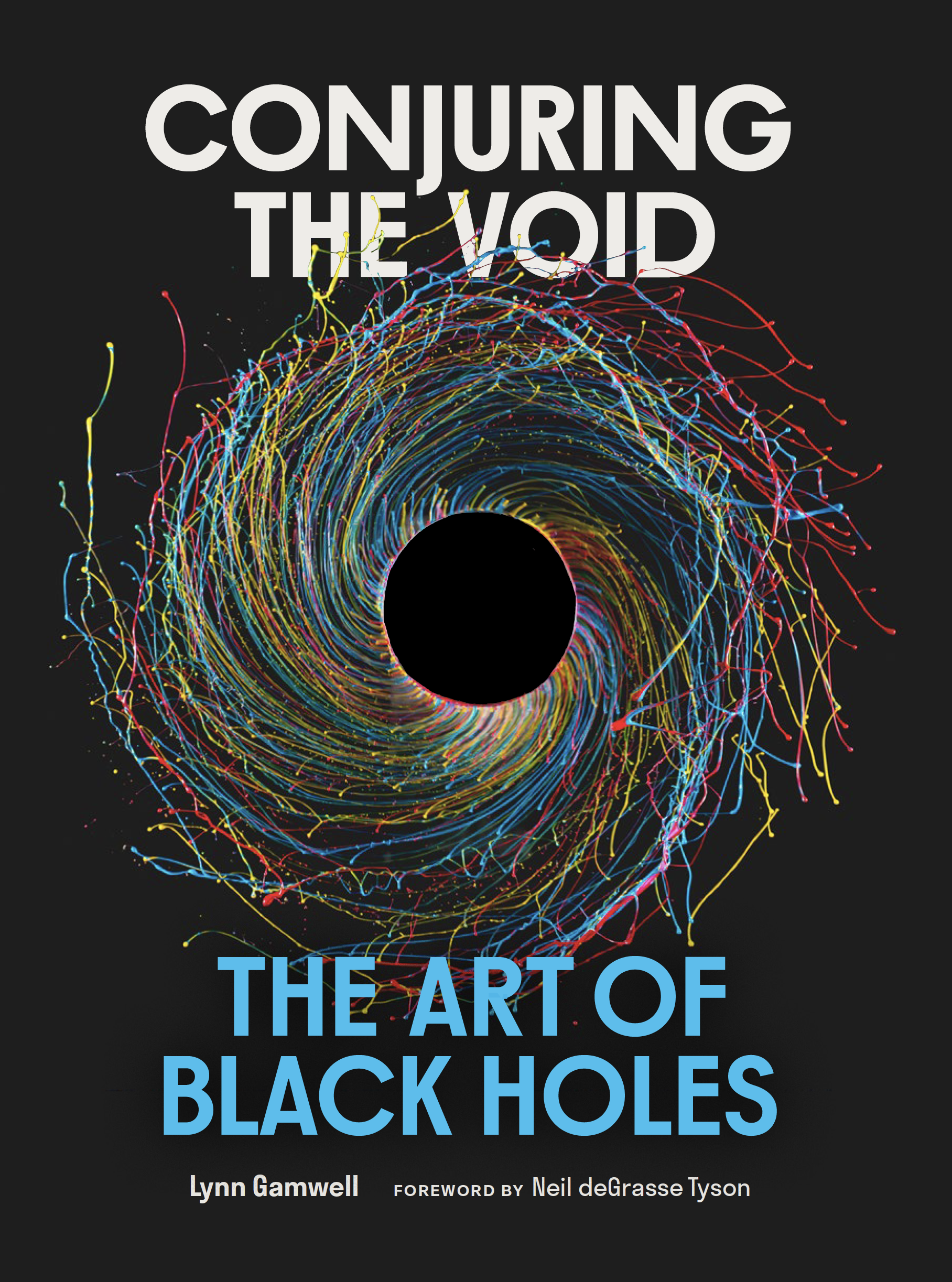

Foreword: Conjuring the Void: The Art of Black Holes

From Conjuring the Void: The Art of Black Holes by Lynn Gamwell

The role of the artist as the scientist’s companion, and that of a scientist as the artist’s muse, has evolved over the centuries, with the biggest shift occurring after photography was invented in the nineteenth century. For the first time, scientists no longer needed artists to capture objective reality. And gone were the risks of perception errors when portraying actual objects as art. Instead of thwarting artistic creativity, photography would, of course, free artists to create their own impressions of things—on purpose, and not as a shortcoming of their ability to capture reality.

The artist still offered value to the scientist. Not as before, but as a conduit to all that fell beyond the reach of the scientist’s capacity to measure. Planetariums, until recent decades, employed artists to convey in space

shows all that was yet to be photographed. Before we ever landed on the moon, what might those terrains have looked like if you were there? What would Jupiter look like when viewed from Europa, one of its icy moons? How might Saturn appear when seen through the thick atmosphere of its largest moon, Titan? Or if you were standing on Mars, what might a solar eclipse look like with either of its two tiny moons, Phobos or Deimos? Informed by science, these visualizations helped to propel our imaginations forward. In the presence of this visionary art, we were compelled to feel the vistas rather than just describe them from their physical properties.

Alas, images from space probes and planetary landers have further diminished the role of artists. And by way of modern detectors, we can “see” light that would otherwise be invisible to the unaided eye, coming to us from every other band of the electromagnetic spectrum—radio waves, microwaves, infrared, ultraviolet, X- rays, and gamma rays. What can the artist now do for science? Not to worry. There’s plenty left in the cosmos to be visualized. How about the Big Bang itself? Or the multiverse? Or how about dark matter, dark energy, and black holes, none of which emit photographable light, yet all greatly influence their environments, with consequences to the evolution of the universe itself.

In particular, the maw of a black hole is legendary. So are the invisible distortions of spacetime that surround it. Both are in desperate need of scientifically informed art to represent them. The inevitable accretion disk that spirals down the black hole while flaying nearby stars is also something that we’ve never witnessed close up. Nor can we see what’s causing the jets of material that spew forth from them. Our telescopic resolution is insufficient to see these details. All we measure is the blended light of the spiraling material, just before it descends out of view. The basic laws of thermodynamics, when combined with the orbital mechanics of gas flows, tell us what should be happening there, as our artists provide visual conduits to this front-row seat in the universe.

Meanwhile, as our computer models and attendant computer graphics of cosmic phenomena get better and better, the scientist becomes the artist. But the artist, still inspired by the universe, continues undaunted. As with the advent of photography, artists are now free—not to illustrate black holes and spacetime, but to react to them. This gift to us all is not art imitating life, but art extending life into new dimensions on the cosmic continuum of creativity.

In compiling this collection of images, Lynn Gamwell combed the world, if not the cosmos itself, to display what extraordinary efforts artists and scientists alike have invested in portraying black holes. Enjoy the art. And along the way, learn some astrophysics, too.

Neil deGrasse Tyson